“Art is something that helps me overcome my weaknesses and face the world with a sense of hope.”

Born as the youngest of four children in 1929 in Matsumono City, Japan, Yayoi Kusama comes from a prosperous and conservative family. From the early age of ten, Kusama experienced hallucinations of repetitive patterns and aureoles around objects, that have plagued her ever since. The artist remembers, that she first started to draw in that period, establishing that her mental illness became central to every aspect of her work, from her imagery to her working process. Kusama was even able to trace back the emergence of the Infinity Nets and the polka dot motifs to those earliest hallucinations. Before experimenting with abstraction from 1950 onwards, Yayoi Kusama was trained in traditional Nihonga painting, which combines Japanese techniques with elements of 19th century European naturalistic subject matters.

In 1958 Kusama moved to the US, strongly believing that her future lay there. Arriving in New York with more than thousand drawings, very little money and barely speaking English, Yayoi Kusama ambitiously strove to become a successful artist and support herself financially through selling her art. What followed was a period of enormous artistic development but also of personal struggle and financial hardship. It was within the first eighteen months of her decade in New York, that Kusama expanded her formats from small scale watercolour abstractions to completely different proportions. She began covering miles of canvases, houses full of objects, clothes and even people with her repetitive and obsessive patterns – the Infinity Net and the polka dot – thus developing her signature style. Her vast monochrome paintings resonated with contemporary European artistic movements, among them the German Group Zero, whose founding members were Heinz Mack, Otto Piene, later joined by Günther Uecker. Even though Kusama never agreed to become a member of an artist group or movement, she connected with virtually all major figures of the time, including Andy Warhol, Frank Stella, Claes Oldenburg and Lucio Fontana, but especially with Donald Judd and Joseph Cornell, sharing an intimate relationship with both. In the early 1960s Kusama took her idea of patterns expanding beyond her canvases to another level and started with a series of sculptures and installations, called Accumulations. Covering Household objects like ironing boards, ladders, sofas and chairs with stuffed phallic protrusions, Kusama’s artworks offered a clear feminist critique of a world dominated by male gender.

Kusama’s work is often seen as a precursor to the work of the Pop-Artists which moved in the same circles in New York. To Kusama, the techniques of silkscreen printing and airbrush and the clean lines of industrial and commercial art taken up by the Pop-Artists were – in her own words – the embodiment of a “mechanized and standardized” environment of a “highly civilized America”. The Pop-Artist most mentioned in connection with Kusama is Andy Warhol. In Kusama’s first publicly exhibited installation One Thousand Boats Show of 1963 at the Gertrude Stein Gallery, the artist covered the whole room with a wallpaper showing the motive of her boat sculpture in a repetitive serial pattern. There is an undeniable visual similarity to be found in Andy Warhol’s Cow Wallpaper of 1966, published three years after Kusama’s ground-breaking work. Concerning the relationship between the two artists Kusama once noted: “We were like two mountains”. The divergence in their approach is to be found at the core, Kusama’s hand-making of repetitive patterns is directly connected to herself and her obsession, while Andy Warhol propagated the merging of industrial

production and mass marketing with contemporary art.

Yayoi Kusama suffered from the unfairness, that male American artists enjoyed huge success reworking her ideas, while she was marginalized due to her gender and ethnicity. Even though Kusama’s overtly sexual visual vocabulary and her feminist stance in art caused scandals and were talked about widely, there was a curios reluctance of art critics to discuss this aspect of her work in print.

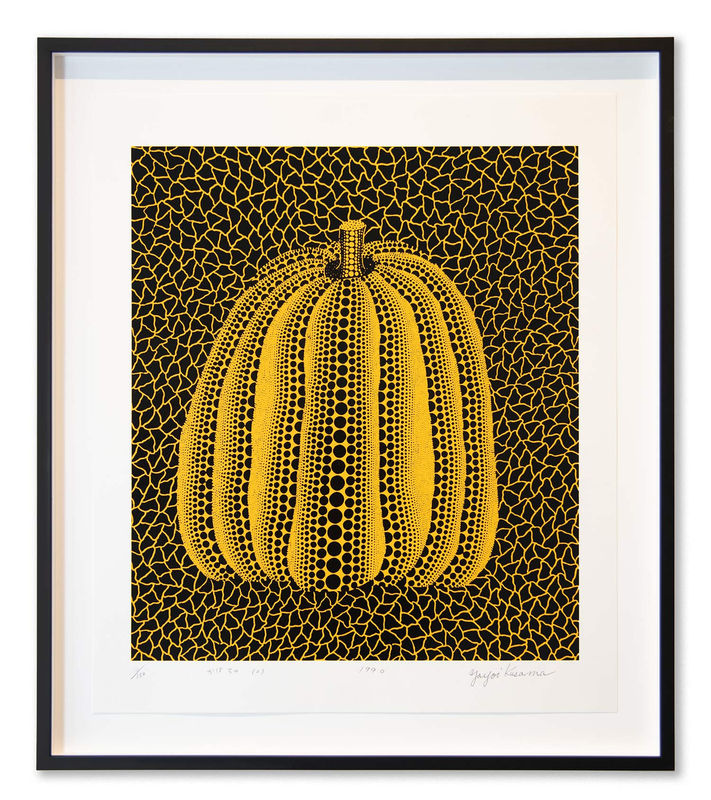

Yayoi Kusama’s hors concours participation in the Venice Biennale 1966 with a huge installation of mirrored plastic balls titled Narcissus Garden, caused a huge scandal that was echoed in international media. By offering to sell off the installation piece by piece to visitors, she revealed the economic undercurrent of international art exhibitions. Facing financial hardship and fading interest in her happenings in New York, Kusama moved back to Japan in 1973. In the mid 1970s she settled in an apartment in a private clinic for mental illness in Shinjuku, Tokyo, where she still lives, working in her nearby studio every day. During the 1970s and ’80s, Kusama began to intensely work with her famous Pumpkin motif. According to the artist, the motif is connected to childhood memories and she first began sketching pumpkins as an elementary school student. But only after her move back to Japan it gained a prominent place in her work.

For nearly two decades after her move to Japan, America and Western Europe seemed to have nearly forgotten about her. Re-emerging in Europe with her participation in the 45th Venice Biennale in 1993, Yayoi Kusama was the first female artist and the first Japanese artist ever to hold a solo show in the Japanese Pavilion. Her presentation consisted of a retrospective selection of works and an installation of a mirrored room, filled with tiny yellow pumpkin sculptures dotted in black, in which the artist sat in a long magician’s robe and pointed hat of the same colours. Kusama has been fascinated with ideas of endlessness in space and vision throughout her career. She first used mirrors in the mid-1960s in her large-scale installations Infinity Mirror Room – Phalli’s Field, 1965, and Kusama’s Peep Show (Endless Love Show), 1966. Although these early works presented a more sexually oriented language, the way in which the viewer became part of the phenomenological environment, experiencing endlessly multiplied forms, is comparable to her later Infinity Mirror Room. Kusama has underlined the importance of the role the viewer plays in her rooms and how he or she continually experiences the work in a new way: “One is more aware than before that he himself [the viewer] is establishing relationships as he apprehends the object from various positions and under varying conditions of light and spatial context […] For it is the viewer who changes the shape constantly by his change in position relative to the work.” Her 21st-century renditions of these mirrored installations are often held in darkened rooms lit with twinkling lights, reminiscent of a galaxy of stars and transporting viewers to a world far beyond our own.

Yayoi Kusama translated her obsession with the pumpkin into her sculptural work on a grand scale. In 1994 she created her first giant Pumpkin for the Benesse Art Site on Naoshima island, Japan, where the spotted yellow sculpture rests in open air beside the sea on its own jetty. Visually compelling, the sculpture became an instant success and played a pivotal role in Kusama’s career and contemporary art legacy. A second giant Pumpkin, coloured red with black dots, was installed on Naoshima island in 2006. An eight-foot-tall sculpture of a polka-dotted Pumpkin was installed outside the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, in Washington, DC to announce her 2017 retrospective exhibition. “It seems pumpkins do not inspire much respect,” Kusama once said. “But I was enchanted by their charming and winsome form. What appealed to me most was the Pumpkin’s generous unpretentiousness.”

Today Yayoi Kusama is one of the most prominent female artists in the world. Her paintings, sculptures and installations have been exhibited in the most important museums around the world and are part of some of the most prominent museum collections.